Chapter 16: The Late Middle Ages

Introduction

Several fundamental changes occurred in Europe between 1300 and 1500 that differentiated this period, known as the Late Middle Ages, from the High Middle Ages (1000-1300). Perhaps most significantly, instead of expanding for 300 years, European population declined for most of the 200-year period due to famine, war, and disease, especially plague. A thousand years earlier the Roman Empire had encountered a similar demographic collapse during the 200s CE, a period sometimes referred to as the Crisis of the Third Century. Similarly, Europe and especially the Holy Roman Empire would encounter another collapse during the 1600s with the Thirty Years’ War, the most deadly war that Europeans had ever encountered up to that time.

In all three cases––200s, 1300s, and 1600s––demographic decline did not result in the destruction of these civilizations, but rather sparked a restructuring. In the case of the Late Middle Ages, the widespread loss of life coincided with significant achievements in art, architecture, literature, education, technology, and the organization of society. These achievements not only contributed to the loosening of the rigid social hierarchies of the High Middle Ages, but they also transformed Europeans’ relationship with non-Europeans. They cemented the cultural differences between Europe and Asia because they deepened the cultural distinctiveness and collective identity of Europeans. Instead of being a cultural backwater that suffered from second-rate technology, illiteracy, and limited opportunities for education, and poor social organization, Europeans became increasingly educated, literate, and organized, as they continued many of the developments from the High Middle Ages.

A broader spectrum of society, including a growing middle class, increasingly exploited new technologies, such as the printing press, improved metallurgy, and the discovery of new navigational tools, to advance their wealth and comfort. Even though the economy was contracting overall, the possibilities of attaining an improved standard of living improved as books became more available, markets continued to develop, and new occupations emerged in urban settings. Accompanying these trends was the advent of gunpowder technology and new methods of warfare, which sometimes threatened the power of established authorities, such as kings and popes, and other times allowed those same authorities to expand their dominions. Consequently, by 1500 Europeans were armed with new weapons, new knowledge, and new means of accessing resources across the globe as they entered into the Early Modern period (1500-1800).

The Transformation of Warfare

At the intersection of many of these changes was the transformation of warfare. Initially, the changes in warfare were more related to recruitment and the organization of members of the middle and lower classes than they were with the introduction of new technologies, such as gunpowder. During the last two centuries of the Early Middle Ages and during the entirety of the High Middle Ages, cavalry charges constituted the most effective battlefield tactic. Historians often refer to this method of warfare as “mounted shock combat” because the shock of the charge from mounted knights produced chaos and confusion on infantry formations. Although the training and expense of mounted shock combat were significant, the general consensus was that this method of fighting was so effective that kings could reasonably expect an army composed of 2,500 cavalry to overwhelm an infantry force four or even ten times that size, especially if that infantry lacked intensive training, discipline, and organization. Mounted knights could move swiftly to exploit gaps in disorganized infantry formations, as they did at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. An investment in knights often seemed worthwhile to kings, and the fondness that the European nobility had for chivalric literature only reinforced this attachment to fighting on horseback. A king who invested heavily in maintaining an army of loyal knights by conferring land and titles on warriors could assemble a formidable and effective fighting force in order to gain control of more land, people, and taxes.

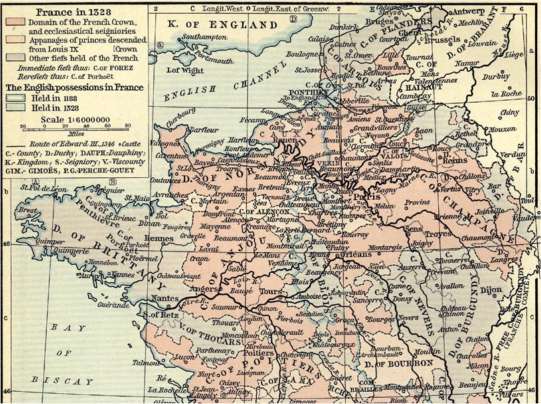

Such was the plan of King Philip the Fair of France (r. 1285-1314), who set his sights on the conquest of Flanders in the last decade of the thirteenth century. At that time Flanders, located in modern Belgium, was the home of the largest concentrations of cities north of the Alps. With a dense population engaged in textile production and trade, the County of Flanders represented a tempting opportunity to expand the growing dominions and tax revenues of the French crown. Like so many other parts of the early medieval Frankish Empire, Flanders was nominally part of the Kingdom of France. However, in practice, the territory had been under the autonomous control of the powerful counts of Flanders since the fragmentation of Francia in the 900s.

After locals in Bruges massacred French occupying forces in May 1302, the cities of Flanders banded together to field an army composed almost entirely of 8,000 to 10,000 infantry. These Flemish militias were unusually well-trained to handle pikes and other weapons, such as crossbows, that were well-suited to the defense of their cities. They knew the King of France would seek retribution for the Bruges rebellion, and they prepared to defend their land. They intercepted the invading French forces at Courtrai on July 11th, 1302. Led by one of France’s most experienced commanders, Robert of Artois, the French had defeated the Flemish handily five years earlier and apparently expected a repeat performance at Courtrai in 1302. However, the battlefield did not favor cavalry charges. It was marshy and uneven. Although the French had horses specially bred for cavalry charges, their steeds failed to build enough momentum, and the well-trained Flemings did not break ranks in their defensive formations. They routed the French attacks, killed Robert of Artois, and hung the spurs of the French knights in a local church to commemorate the victory, often referred to as the Battle of the Golden Spurs.

Narratives of this victory of middle-class militias over the forces of the French crown became part of the collective identity of the peoples who later called themselves Belgians. Similar victories by commoners against kings and their mounted nobles occurred increasingly over the next two hundred years and beyond. Scottish, English, Portuguese, and Swiss commoners won resounding victories against cavalry charges at Bannockburn (1314), Crecy (1346), Aljubarrota (1385), and Grandson (1476). Generally, these victories pitted commoners in a defensive position using pikes, halberds, and other ancient weapons combined with some sort of missile weapon, such as the crossbow. Sometimes, the commoners fought alongside a significant contingent of cavalry, as they did at Bannockburn, Crecy, and Aljubarrota; other times, such as Grandson and Courtrai, the commoners had little or no noble support.

Some monarchs took advantage of the growing possibilities of commoners in warfare; others maintained a commitment to chivalric norms that emphasized the nobility of men fighting with blades and lances on horseback. One of the earliest monarchs to innovate was Edward I of England (r. 1272-1307). During the late 1200s he launched an expensive and protracted campaign to gain control of Wales, where he encountered archers who wielded a powerful weapon, the longbow. Although it is somewhat unclear how much Edward I actually employed English archers in his battles against the Scots and Welsh during the late 1200s and early 1300s, he encouraged his English subjects to practice archery while employing Welsh archers. Although Edward’s son and successor, Edward II (r. 1307-1327), eschewed the longbow, his grandson, Edward III (1327-1377), though a champion of chivalric ideals, realized the potential of the missile weapon early in his 50-year reign.

Attempting to reverse a humiliating peace treaty signed with the Scots during the minority years of his reign, Edward III won decisive victories against numerically superior forces of Scots at Dupplin Moor (1332) and Halidon Hill (1333). Although Edward III did not participate personally in either battle, contemporaries often viewed victory in war as a sign of divine approval. If they were correct, God approved of Edward III for most of his long reign, when England fought a much larger and wealthier French crown during a conflict known as the Hundred Years War (1337-1453). The English successfully integrated the longbow into a repeatable system of warfare at the battles of Crecy (1346), Poitiers (1356), and Agincourt (1415).

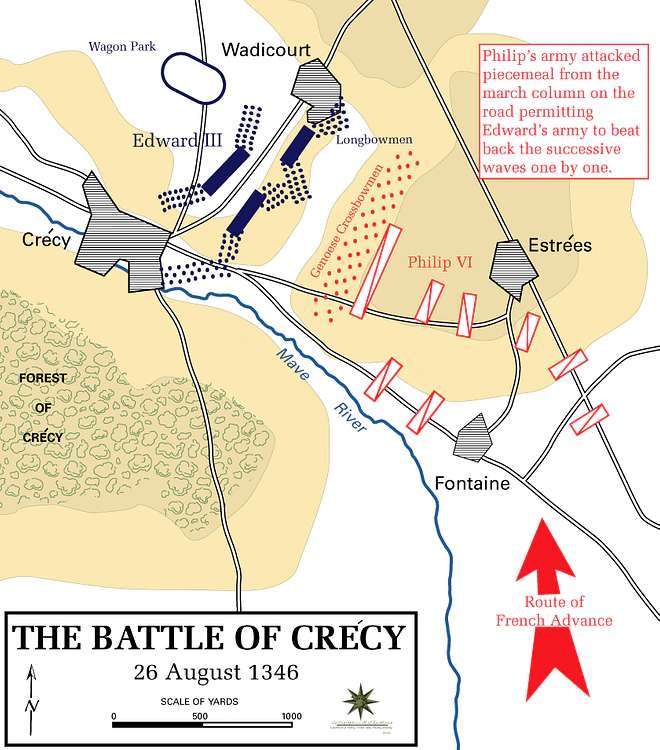

This system involved the placement of the longbow on the edges of a crescent-shaped formation, preferably protected from cavalry charges by terrain. As the French had experienced in the marshes near Courtrai, knowledge of terrain could determine the outcome of a battle. At Crecy, the English were in a fairly desperate situation. They were woefully short of supplies while their Flemish allies started fighting among themselves and then failed to reach the English host. Other reinforcements from England also failed to materialize. Edward III, commanding the troops in person, situated them on one of the many hillsides that dotted the countryside in Normandy. The chosen terrain prevented the French from attacking from the rear or the flanks. They had to face the English head on.

Although the French had hired a large contingent of Genoese mercenaries as crossbowmen, they were no match for the longbow because of the differences in the rate of fire. The Genoese retreated just as the French cavalry began its charge. The horses trampled the mercenaries before facing a barrage of enfilading fire from the archers on the crescents as they tried to ride to the top of the hillside. Those who made it up the hill faced standing men-at-arms with pikes, halberds, and swords. The English had established a very strong defensive position that the cavalry charges could not penetrate. As the French losses mounted, they began to retreat. However, Edward III had held a cavalry charge in reserve, and as the French retreated, the English knights hunted down many of the would-be survivors.

Ten years later, the longbow proved equally effective at the Battle of Poitiers (1356). Although this battle differed substantially from the Battle of Crecy, the English once again used a combination of well-positioned longbows, carefully selected terrain, and standing men-at-arms. The French sought to reduce the impact of the longbow by wearing stronger plate armor and by dismounting some of their cavalry because horses were highly susceptible to injury from the arrows. These alterations proved somewhat effective but insufficient. The English captured the French king, John I, and by 1360 the two sides negotiated a peace treaty (known as both the Treaty of Brétigny and the Treaty of Calais) so favorable to the English that the French eventually broke the agreement and resumed the war. The treaty included enormous payments of silver to Edward III and ceded sovereignty over much of southern France, Aquitaine, to Edward. In return, the French king returned briefly to France, and Edward III promised to give up his claim to the French crown.

Because the longbow and the English system of war had proven so effective in these encounters, the French essentially avoided full-scale battles over the coming decades. Instead, they periodically harried invading English armies intent on terrorizing the local French peasants in a tactic known as the chevauchée, a burning and looting of the countryside. These English invasions of France were both costly and ineffective. Almost as unpopular in England as they were in France, the English campaigns of the 1370s depleted the royal treasury with no territorial gains to show for it. Despite the success of the middle-class archers in the 1340s and 1350s, Edward III’s reign ended with the English divided and all but incapable of mounting effective military actions in France.

Despite the fading taste for war, the English commoners celebrated the longbowmen in ballads, songs, and legends. The archers mostly consisted of members of the middle class, known as yeomen. The longbow was the preferred weapon of the outlaw hero, Robin Hood. Although its origins are somewhat obscure, the legend became a popular folktale by the 1370s. Similar to the legend of William Tell in Switzerland, Robin stood against the tyranny of those in positions of power. The emergence of these commoners as heroes in folktales coincided with the growing success of middle-class warriors in battles across Europe. It also coincided with the growing power of the middle class in the economy and in politics as we will see in the following sections.

Ironically, it was not in England but in France where the most celebrated commoner won the most important victories of the Hundred Years’ War. Generally referred to as Joan of Arc (1412-1431) in the English world and Jeanne d’Arc in France, the young peasant girl who led French troops into battle in 1429 was not known for her warrior prowess. Instead, she maintained an unwavering conviction that God had sent her to save France from the English. The quick succession of victories that the French forces secured with her in a visible position of leadership resuscitated the morale of French troops. Joan participated in strategy sessions and battlefield encounters throughout 1429 and 1430. Although English allies had captured, tried, and burned her by 1431, her successes became the stuff of legend. Her ability to remain undaunted by her humble origins and the prejudices against women that were particularly pronounced in the military made her one of the most impressive non-noble warrior heroes of the period.

Historians have sometimes characterized the increased effectiveness of non-nobles in the wars of the 1300s and 1400s as revolutionary. While the size of armies grew and the tactics involved became more varied and sophisticated, the changes occurred gradually and incrementally. Innovative kings, such as Edward III, realized that they did not have the knights and customary resources to compete in chivalric contests with the French crown. Consequently, they recruited outlaws and sometimes conscripted commoners, including imprisoned felons, to field large, effective fighting forces at a lower cost. Although the older, chivalric custom of knights holding other knights captured in battle for ransom continued, longbowmen and pikemen fought to kill. They were not looking to hold a knight for ransom. The casualties at Courtrai in 1302 and Crecy in 1346 were in the thousands. And while warfare was becoming more deadly as organized bands of commoners became more integral to military tactics in the 1300s, other factors were at work that caused the population of Europe to drop in the millions during the 1300s.

Famine, Plague, and Assaults on Authority

For millennia warfare has often been a vector for outbreaks of famine and disease. Invading armies routinely destroyed crops while spreading diseases, such as dysentery, that often erupted in military encampments. However, other causes were at work when the Great Famine arose across most of northern Europe from 1315-1317. Such a widespread crop failure had more general causes than even the largest of armies of the period could spread.

Even before widespread famine engulfed much of Europe north of the Alps in 1315, grain harvests were beginning to falter in the late 1200s and early 1300s. The increased population that had characterized the High Middle Ages necessitated more intensive cultivation of the land. Parts of France, for example, were more populous in the early 1300s than they were in the twentieth century. Consequently, crop yields declined as the average size of peasant holdings decreased. These smaller plots of land necessitated more intensive farming, which depleted nutrients in the soil. Exacerbating this situation, average temperatures dropped, growing seasons shortened, and rainfall increased. Not only were the yields smaller, but because of reduced exposure to sunlight, the crops were also less nutritious when consumed.

Writing in the early 1300s, an English monk, Johannes Trokelow, recognized the impact of the increased rainfall and the cooler weather on the price of grain. Although he was only familiar with rising grain prices in England, the pattern held across much of Europe where a 300% increase in grain prices was common. Without the ability to afford grain in the markets, peasants ate their seed corn, traditionally used to plant the next year’s crop, and slaughtered their livestock. According to rumors, some commoners hungrily eyed their pets and perhaps even their children. Even the English royal family experienced shortfalls with its provisions; King Edward II was facing his own problems including a civil war led by his cousin, Thomas of Lancaster. But these battles and their armies were fairly small. The impact of war on the English peasants working the land was relatively local and contained. Consequently, the Great Famine of 1315 was likely the result of a combination of soil exhaustion and non-anthropogenic climate change; volcanic eruptions may have filled the atmosphere with enough particles to reflect the sun’s warmth. In any case, poor harvests were widespread, and Europe lost an estimated 5-10 million people.

The decreased supply of grain had a devastating effect on Europe’s livestock. Desperate for food, peasants slaughtered draft animals. Without grain or necessary fodder, many livestock starved; some drowned due to the increased rainfall. With immune systems compromised by lack of nutrition, sheep and cattle contracted diseases such as murrain and anthrax. It is likely that humans acquired some of these diseases through zoonotic transmission, where a pathogen, such as a virus or parasite, jumps from an animal to a human. Zoonotic transmission has been linked to the various coronaviruses in the twenty-first century, most recently from bats to humans. Although anthrax spores have been uncovered in some mass graves from the 1340s, the most likely explanation for the particular outbreak of plague, known as the Black Death, is that it arose from a combination of zoonotic and human-to-human transmission of the Yersinia pestis bacterium.

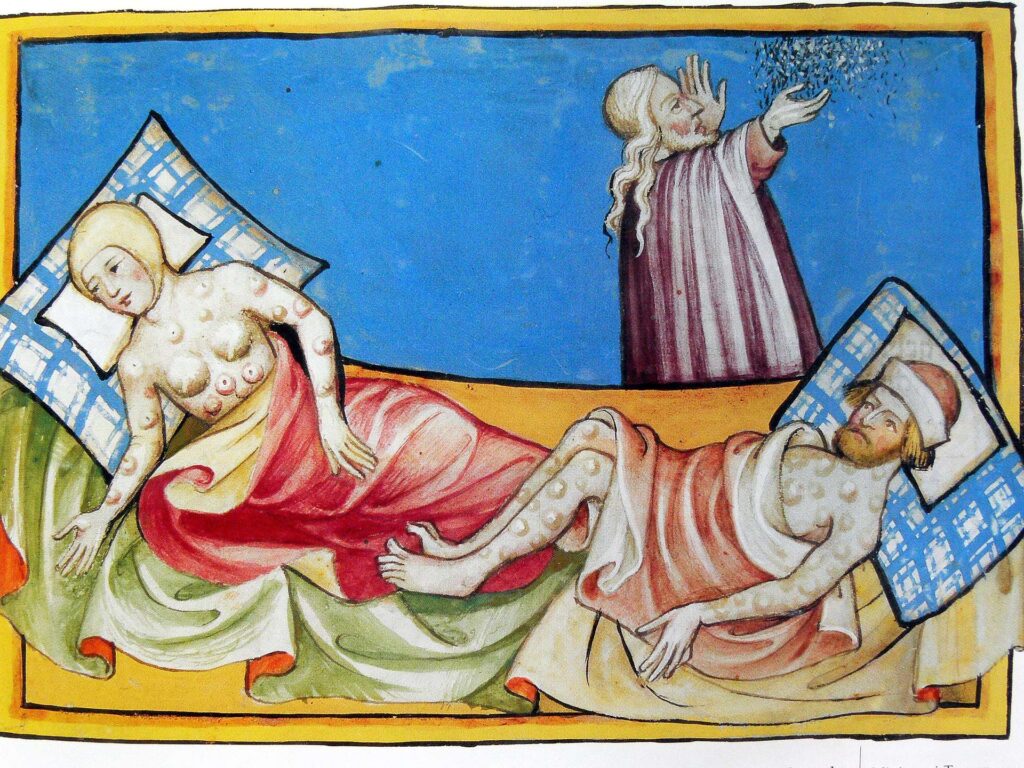

Historians still debate as to exactly which disease or diseases the Black Death consisted of, but the prevailing theory is that it was a combination of bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic plague. Fleas transmitted bubonic plague, whereas pneumonic and septicemic plague occurred as pathogens traveled from human to human either airborne or through bodily fluids. In the unsanitary conditions of medieval Europe, both rats and fleas were common pests. In turn, many victims of plague developed flu-like symptoms and transmitted the sickness by coughing or sneezing. Once infected, a person could also expect swelling, called buboes, near the groin or joints. Eventually, the buboes turned dark, ruptured, and emitted unpleasant odors.

These were the commonly reported symptoms of the pandemic that swept across Europe in the mid-1300s. The Black Death refers to this specific outbreak of plague that Europeans faced between 1347 and 1351. During this period entire villages died of the disease while other localities suffered relatively few deaths. The uneven distribution of mortality rates was likely due to poor harvests, compromised immune systems, and the lack of efficacious medical treatments. Although research into the etiology of the Black Death is ongoing, the most widely accepted explanation is that this deadliest of pandemics in medieval and early modern history began in the Mongol khanates and spread west.

As the disease entered Europe in the late 1340s it generally spread from south to north. Some of the earliest epidemics were in Constantinople, Athens, and Sicily. A common narrative claims that Genoese merchants contracted the plague at the siege of Kaffa in the Crimean peninsula in 1346 and brought it back to Italy by 1347. Within five years it had reached Scandinavia, Scotland, and Ireland. Some cities lost over half of their population, and somewhere between 20 and 40 million Europeans likely perished during the Black Death as the overall population dwindled to approximately 60-80 million. Further outbreaks of plague occurred in 1361-2 and in 1369. They continued to erupt periodically and locally for the next 350 years.

One relatively effective response to the plague was the implementation of quarantines. The word came from the Italian practice of isolating the infected for forty days, quarantina in Italian. City governments locked those who had plague symptoms in their homes, and they sometimes placed whole neighborhoods or districts under quarantine. In the countryside, people refused to travel to larger cities and towns out of fear of infection. Cities tended to be incubators of disease even in healthier times.

Less effective responses were more common. Some communities engaged in prayer, practiced mortification of the flesh, or searched for scapegoats. Groups of penitents, called Flagellants, roamed the countryside, villages, and towns, whipping themselves and begging God for forgiveness. They operated on the belief that the sins of humanity were the root cause for the scourge of plague that God had sent. Their numbers sometimes swelled into the thousands, and they forced observers to join them. By 1349, Pope Clement VI (r. 1342-1352) condemned them. His exact reasons were somewhat mysterious, but the Church typically took a dim view of Flagellants. The authorities issued a second rebuke against them in the early fifteenth century as well. Despite these attempts at suppression, Flagellants continued to appear periodically, and those who did not share their concerns, especially Jewish communities.

Flagellants were not the only ones to blame Jews for the plague. Building on the murderous anti-Semitism that had begun in earnest during the period of the crusades, Jews were often victims of the intensified religious enthusiasm that followed the outbreaks of plague. A frequent accusation leveled against Jews was that they had poisoned wells. Locals massacred tens of thousands of Jews in the Iberian peninsula during the second half of the 1300s. Generally, these pogroms coincided with the appearance of plague in 1355, 1360, 1365, and especially 1391.

Gradually, plague epidemics became more local and less frequent, but the disease became endemic to Europe and, therefore, kept the population low for generations. It was not until the mid-fifteenth century that the overall population started to rise again. Even then, plague persisted throughout Europe with outbreaks in London between 1665 and 1666 and in Marseilles between 1720 and 1723. In both cases, the loss of life was substantial with 100,000 deaths in both places. The mortality rates for plague were very high, twenty to forty times higher than the rates for COVID-19.

The sustained decline in population during the 1300s and 1400s had profound effects on the distribution of wealth in Europe in terms of food prices, rents, and wages. Although food prices initially rose as the widespread loss of life disrupted markets, by the 1360s grain production rebounded, and markets stabilized. With fewer mouths to feed, grain prices declined throughout most of Europe. The decline in population also affected wages. Since there were fewer people to work the land, wages rose rapidly for those who had survived the plague. There was a labor shortage. Desperate for laborers, some landlords offered attractive (low) rents and high wages with no servile dues to work their estates. Some peasants and serfs fled their existing holdings for more beneficial offers. Consequently, this combination of lower food prices and rents, on one hand, and higher wages, on the other, provided unprecedented but generally modest opportunities for upward social mobility among the laboring classes.

Similarly, the labor shortage benefited lower and middle-class women. For roughly a century after the plague, women had more legal rights in terms of property and land ownership, as well as the right to participate in commerce. In England and the Low Countries some women lobbied for and received the status of femme sole, which gave them the right to have the courts treat them as independent legal entities, instead of the legal dependents of their husbands or deceased husbands. However, this status did not always work to their advantage, as the courts tended to treat them with prejudice. Some women were able to join craft guilds for a time, something that was almost unheard of prior to the Black Death. The reason for this temporary improvement in the legal and economic status of women was precisely the same as that of their male counterparts: the labor shortage.

Meanwhile, the literature of the period reflected the aristocracy’s fears of losing their privileges. During the labor shortage, they paid more for labor, but they collected less as tenants sought the most beneficial terms for work and rent. Without knowing economic theory, surviving commoners took advantage of the slackening demand for land due to the dwindling population. With lower rents and higher wages, the Black Death ushered in powerful forces for social change, including increased social mobility (the ability to improve one’s socioeconomic position) and the decline of serfdom (more legal freedom).

The Black Death accelerated social changes apart from the improvement of economic conditions for commoners. Challenges to traditional authorities, the Church and the nobility, were already underway when Giovanni Boccaccio penned his masterpiece, The Decameron, while plague was ravaging his native Florence between 1347 and 1350. The 100 stories in his work mocked members of the Church and the nobility, in addition to questioning longstanding practices related to religious intolerance and even patriarchy. Although the commoners’ defiance of the French nobility at Courtrai four decades before the Black Death indicated a willingness to defy aristocratic dominance, this lack of social deference and obedience became more pronounced by the second half of the 1300s. The rigid hierarchy that had characterized Europe prior to the Late Middle Ages was under attack.

Boccaccio’s depiction of the unruliness of common folk was not unique to southern Europe or the Italian peninsula. By the 1370s, Geoffrey Chaucer had started writing his Canterbury Tales. Likely inspired by Boccaccio’s Decameron, Chaucer’s poem about pilgrims on their way to Canterbury mostly consisted of eclectic tales that echoed many of the sentiments Boccaccio expressed a generation earlier. Both men drew attention to corruption within the Church; Boccaccio focused on the lechery of religious figures and Chaucer, their greed. Both works also included the account of the Marquis of Montferrat, Gualtieri or Walter (in English), a childish and depraved man, who demanded unconditional obedience from his previously impoverished wife, the noble peasant, Griselda. While neither work went so far as to preach against the deeply entrenched patriarchy that afflicted European society and culture, both writers broached the sensitive subjects of gender and marriage relations, especially the authority that husbands had over their wives. By depicting the mentally tormented wife, Griselda, whose husband claimed to kill her children, as the moral superior of her warped, aristocratic husband, Boccaccio and Chaucer opened up discussions related to the superiority of men and nobles.

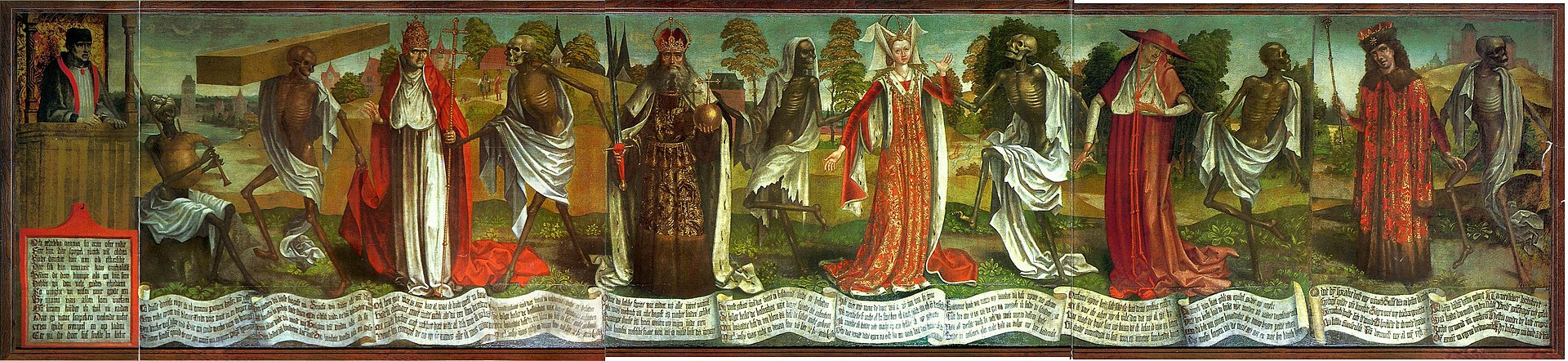

The Danse Macabre or Dance of Death was circulating in Europe for decades before the Black Death, but its depiction became more frequent afterwards. In this illustration, the highest members of society (pope, emperor, empress, etc…) were dancing to their graves, as did commoners. The message was clear: everyone shared a similar fate at the end of their lives.

This questioning of the privileges enjoyed by a male-dominated aristocracy was part of a more general leveling trend that arose in the 1300s. Sometimes this sentiment was more subtle and implied, as in the depictions of the Danse Macabre. The Dance of Death was a relatively common artistic trope that featured skeletons of all walks of life, often leading a hierarchical procession of society toward a common fate: the grave. And sometimes the leveling trend manifested in violent attacks on the nobility. In 1358, the peasants in areas surrounding Paris joined with members of the middle class, and even the Mayor of Paris himself, to attack the manors and families of the French nobility. Accounts of this bloody uprising, known as the Jacquerie, struck fear into the minds of the nobility. Similarly, the commoners surrounding London executed the archbishop of Canterbury and the followers of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, in an uprising that left hundreds dead in the city in 1381. Chaucer was likely in the city to witness this event; however, Boccaccio was dead by the time the lower classes of Florence, known as the ciompi, rebelled between 1378 and 1382.

Still, the trend was clear. The middle class was becoming more powerful as common people became warrior heroes, enjoyed more opportunities for economic prosperity, and figured prominently as the moral equivalents or even superiors of aristocrats in artwork, such as the Danse Macabre, or in literature, such as the story of Griselda and the repugnant Gualtieri. Sometimes, commoners exercised their growing power through the emergence of representative institutions, such as the assemblies of Italian republics, the Estates General in France, and the House of Commons in England. However, these institutions lacked the inclusion of the large numbers of lower middle class and poor in society. Consequently, violence erupted as the deference to traditional authorities waned and frustration with exploitative policies and governments and the aristocrats who controlled them persisted. This class tension was a persistent feature of European society well into the Modern (1800-present) period.

The Decline of Papal Prestige

Contributing to this decline in deference to authority was the erosion of ecclesiastical prestige in general and papal power in particular. Given the influence of the Church on the establishment of hierarchy and the transformation of Europe toward a civilization, it is not surprising that its declining prestige incited broader attacks on privileged members of society. The Church had been instrumental in the growth of literacy, the centralization of political power, the perpetuation of hierarchical forms of social organization, and the exploitation of commoners for centuries. Its decline started gradually in the 1200s and picked up speed during the 1300s and 1400s.

The papacy reached the high point of its power and influence during the pontificate of Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216). Soon after his ascent to the papal See, Innocent launched the Fourth Crusade, which not only reduced the power of the pope’s chief rival, the Patriarch of Constantinople, but also enriched Italian merchants. As we saw in the previous chapter, this pope used his power to weaken the Holy Roman Emperor in the Italian peninsula and to force King John of England to recognize him as his feudal overlord. Innocent was trained in canon law and was an able administrator. In 1215, he assembled the Fourth Lateran Council, which defined rituals known as the seven sacraments of the Latin Church and issued a number of other proclamations, known as canons, that strengthened the power of the papacy and the prestige of the clergy in general.

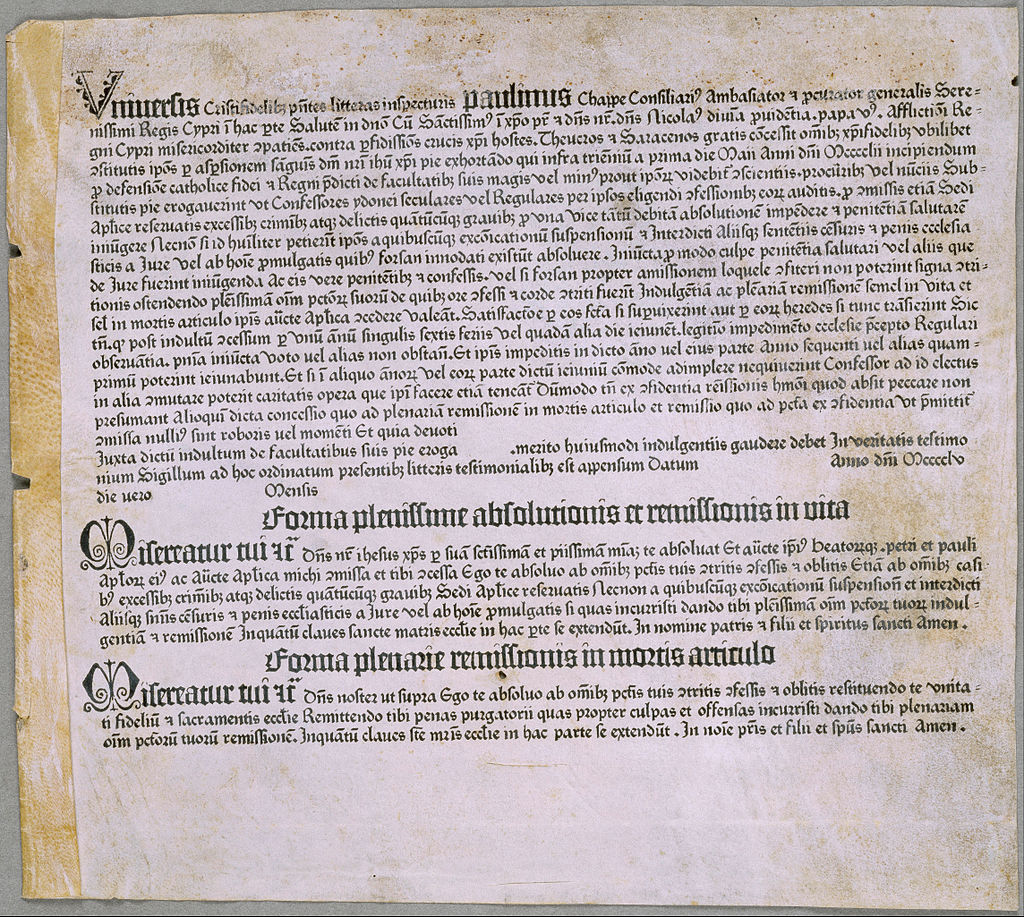

Although the papacy remained very powerful during the thirteenth century, it engaged in practices that gradually eroded its power. The proclamation of crusades for clearly political purposes against the Holy Roman Emperors in addition to the introduction of the sale of indulgences to fund these crusades around 1200 promoted cynicism toward the leadership of the Church. The rise of the Spiritual Franciscans (described in the previous chapter) was one of the most telling signs that criticism of the popes was gaining organized adherents from the most religiously devout members of Christendom. In addition, popes, cardinals, and bishops engaged in an increasingly open effort to profit from their positions of power by selling offices in the Church. This practice, known as simony, weakened claims to moral authority that were instrumental for Church power.

The competition for power between the popes and secular rulers (described in the previous chapter) which had intensified during the Investiture Conflict, became even more intense in the 1300s. By the late 1200s secular rulers were openly willing to defy the popes’ authority to tax and to administer justice in kingdoms, such as France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire. In 1296 Pope Boniface VIII (r. 1294-1303) reacted to initiatives undertaken by the King of France, Philip the Fair (r. 1285-1314), to remove all clergy from the administration of justice in his realm and to impose a tax on the clergy. Boniface issued a papal bull that threatened the king with excommunication if he appropriated Church property without the pope’s permission. Reflecting the growing power of the monarchy vis-à-vis the Church, Philip responded by forbidding the exportation of any goods or currency from France to the Papal States, and he halted the pope’s attempt to raise money in France for a crusade. Although the conflict subsided for a couple of years, by 1301, Philip arrested the pope’s representative at the French court and tried him in royal courts. The pope was outraged and prepared to excommunicate the king. Philip responded by sending troops to the pope’s palace at Anagni, southeast of Rome. Philip’s soldiers and their Italian allies roughed up the seventy-three-year-old pope. Although often referred to as “a slap,” the assault on the pope likely led to his death a month later and was more than a slap.

Subsequent popes heeded the growing power of the French crown. Pope Clement VI (r. 1305-1314) sought to placate Philip, first by enabling Philip’s seizure of the property of the Knights Templar in 1307 and then in 1309 by moving the papacy itself from Rome to Avignon, located more fully within the French king’s sphere of influence. The removal of the papacy from its historical home in Rome significantly weakened the prestige of the papacy. With its imperial lineage, Rome had long signified power and legitimacy even to those Europeans who had little knowledge of the past. In addition to this loss of prestige, the move also cost the popes their control over territory and revenue in the Papal States as the aristocratic families of central Italy took advantage of the departure to enrich themselves. Increasingly, Philip’s rivals, such as the King of England and the Holy Roman Emperor, viewed the papacy as an instrument of the French crown. Avignon itself became synonymous with corruption, and devout Christians lamented the Babylonish Captivity (1309-1377), a reference to the enslavement of the ancient Hebrews in Babylon during the 500s BCE. The implication was that the papacy had become a tool of the King of France just as the Jews became servants of the Babylonian Emperor.

As the French kings leveraged their influence over the papacy by packing the Church with cardinals loyal to the French crown, other European rulers chipped away at the theological foundations of that power. Louis of Bavaria (r. 1328-1347) did not receive recognition as Holy Roman Emperor by the pope until 1328 although he had been King of the Germans since 1314. Angered by this rejection from the pope in Avignon, Louis gave protection and support to Marsilius of Padua (1275-1342), who wrote a persuasive attack on the authority of the popes. Entitled Defensor Pacis (“Defender of the Peace”), Marsilius’s work established a strong theological and historical argument against the popes’ claims to unchallenged authority. While his patron, Louis, invaded Italy in 1326, Marsilius remained in Germany where he persecuted members of the clergy who remained loyal to the reigning French pope, John XXII. The alliance between Louis and Marsilius became part of a pattern of alliance between secular rulers and theologians who collaborated to attack the papacy. This pattern included other theologians, including John Wyclif in the 1370s and 1380s, Jan Hus in the early 1400s, and eventually Martin Luther in the 1500s. These critics both of the papacy in particular and of the corrupt practices of the Church more generally allied themselves with secular leaders who sought to undermine Church power.

In England King Edward III relied less on theologians and more on Parliament to curtail the power of the papacy. In the early phases of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453), emboldened by his victory against the French at Crecy (1346), Edward prompted Parliament to pass the Statute of Provisors (1351) to prohibit the papacy from installing foreigners and especially French clergy to positions of power and wealth in the monasteries and bishoprics of England. Edward’s grandfather, Edward I, had initiated a similar statute in 1306, but given the escalating conflict in France, Edward III deemed it necessary to reinforce the prohibition of such appointments. He and his subjects understood that the popes supported the Valois kings of France, and the English feared that Church revenues harvested in England filled the coffers of their French adversaries. To ensure that the King of England had the ultimate say about any disputes over such appointments, Parliament passed the Statute of Praemunire in 1353 in order to reinforce the king’s jurisdiction over disputed Church appointments.

Tensions between secular and ecclesiastical leaders remained high in England during the 1370s when Edward’s son, John of Gaunt (1340-1399), Duke of Lancaster, took aim at powerful English clergy. As the patron of the Church reformer, John Wyclif, and as the acting head of the monarchy from 1370 to 1377, Lancaster sought to justify the confiscation of ecclesiastical estates in order to fund the war against France. By 1376 Wyclif published a lengthy treatise, De Civili Dominio (On Civil Dominion), that advocated for the confiscation of Church property because of the sinful nature of the clergy. In late 1376 Lancaster seized the estates of the wealthiest bishop in England. As the Church employed its enormous influence on popular opinion, much as it had during the reign of King John in the early 1200s, the duke relented and returned the property in early 1377. More than 150 years later, his descendant, Henry VIII, proceeded with a more ambitious plan and seized the estates of monasteries across England. But the power and prestige of the Church and the papacy were still too deeply entrenched in 1377 for the success of such an ambitious undertaking.

That same year Pope Gregory XI (r. 1371-1378) moved the papacy, along with its secretaries, scribes, and administrators, from Avignon back to Rome in order to salvage the reputation of the office. It was a risky move for a French pope. The crowd in Rome turned ugly, and the pope had to flee to the safety of the papal palace at Anagni, outside of Rome. Within a year he was dead, and the Roman people demanded the election of an Italian pope. Upon the election of Pope the Italian Urban VI (r. 1378-1389), the French cardinals returned to Avignon, where they elected a French pope. For the next four decades Europe had two popes, a development known as the Great Schism (1378-1418), sometimes called “the Western Schism” to differentiate it from the one between the Latin and Byzantine Churches that had occurred in 1054. For the last nine years of this later schism there were even three popes as plans to unify under a single pope backfired.

As rival popes excommunicated the followers of the other pope, so that all of Europe was essentially excommunicated, fears of ecclesiastical censure and of the clergy in general waned. Some took advantage of the divisions within the Church leadership and some of the foundations of its claims to power. One of those critics was John Wyclif in England, who published his critique of the doctrine of transubstantiation, which claimed that the clergy had miraculous powers. In 1382 the English clergy brought Wyclif to trial. They stopped short of proclaiming him a heretic and merely condemned his teachings. Two years later he died, but his critiques of the Church gained powerful adherents after his death. His followers, called Lollards, found protection and support at the court of Richard II (r. 1377-1399) and his queen, Anne of Bohemia (r. 1382-1394).

Upon the death of Anne of Bohemia, her attendants and courtiers carried Wyclif’s ideas to Anne’s native lands in Bohemia, where Jan Hus embraced some ideas and modified others. Like Wyclif, Hus preached in the vernacular against the corruption of the clergy and in support of the ultimate power of monarchs. Unlike Wyclif, he claimed that lay people should be allowed to consume the Eucharist in both forms: the bread as the body of Jesus and the wine as His blood, the latter of which was traditionally limited only to the clergy. This practice, known as utraquism, constituted an attack on clerical privilege and reflected the leveling spirit of the age. At first, Hus’s ideas gained support from the Bohemian monarch, Wenceslas IV (1378-1419), partly because Hussites had widespread popular support in Prague. However, when Hus agreed in late 1414 to travel to a Church council at Constance in modern-day Germany, the emperor had him arrested, despite having assured Hus of his protection. On July 6, 1415, Hus suffered death by burning after being condemned for his heretical teachings.

The burning of Hus coincided with a low point in the prestige of the Church. Divided by three rival popes, Church leaders became desperate to find a solution. In 1409, they had elected the third pope, whose headquarters was in Pisa, about 200 miles north of Rome, in an attempt to withdraw support from the other two popes. It did not work. When the Pisan pope died in 1410, an enterprising cleric, Baldassarre Cossa, borrowed money from the Medici family of Florence to bribe cardinals to elect him as pope. Despite his experience both as a military commander and as an employer of outlaw gangs, Cossa became Pope John XXIII. England, France, Bohemia, and Portugal recognized his claim to the title. However, in 1418, a general council of the Church convicted him on charges of piracy, murder, rape, incest, and other crimes that the Church did not want to mention. Shortly after Cossa’s conviction, secular rulers pressured the other two popes to resign. The council elected a new pope, Martin V (r. 1417-1431), a member of the central Italian nobility. He worked for a decade under the guidance of a Church council, focused on rehabilitating the papacy. However, this rehabilitation was not particularly successful, and by the late 1400s and early 1500s, the corruption of the papacy was more blatant than ever. This deterioration of the papacy was one of the factors that emboldened Martin Luther to challenge the authority of the papacy in 1517.

The Intensification of Religious Devotion

Despite the declining prestige of the leadership of the Church, religious devotion in Europe strengthened as it became more institutionally entrenched throughout secular society and as Europeans became more literate and able to engage with religious texts. The Church had provided non-literate avenues for religious devotion since the Early Middle Ages. Rituals, storytelling, artwork, prayers, processions, and pilgrimages had been staples of the Latin Church since Roman imperial times (c. 300s). Europeans recounted the lives of saints at social gatherings and prayed to these holy figures to intercede on their behalf with the Almighty. They sought cures at the burial sites of saints for the maladies that ailed them. Thus, Christianity had a variety of cultural practices that addressed the spiritual and psychic needs of the population. These practices continued to find favor among large segments of the European population while more literate forms of devotion, such as reading scripture and the lives of saints, increasingly gained traction.

Although the Church leadership claimed authority to define doctrines and beliefs, Christianity proved too malleable for them to control. Various communities, such as Beguines, Lollards, and Hussites, challenged the authorities’ interpretation of religious dogma and practices. In the countryside, peasants found a modicum of freedom to adapt religious practices to their specialized needs. They believed that some saints were adept at controlling the weather, the harvest, and the health of families, especially when the proper rituals were in place to solicit their help. In a later age, the villagers increasingly consulted doctors or almanacs, instead of saints, to guide their practices.

Occasionally, Church leaders traveled to rural communities and expressed shock and consternation at what they found; such was the case when members of the inquisition visited a village near Villeneuve in southeastern France during the thirteenth century. The local women there recognized a dog, Guinefort, as a saint and savior for their unwanted children. Infanticide was likely common throughout the Middle Ages as families struggled to support themselves even with completely healthy children when they had little or no access to effective birth control; although it was emotionally trying, some people with no other recourse resorted to this method of eliminating children they could not support. The local women near Villeneuve brought their infants to a grove in the woods, placed them on a bed of straw, lit a candle, and prayed to Guinefort for relief from their burden. The inquisitors and those who recorded their actions mocked these practices as foolish superstitions. But the local women had adapted their religion and in particular the custom of relying on saints to solve problems to meet the stress and trauma associated with infanticide.

More accepted beliefs found avenues for strong institutional support. The doctrines of transubstantiation, the virginity of Mary (Jesus’s mother), and the nature of the Holy Spirit were just some of the most common beliefs that attracted associations of men, known as confraternities, from across the social spectrum in late medieval Europe. Although there was typically a pronounced religious component to most guilds, their principal focus tended to be on the manufacture and the distribution of commercial goods. By contrast, confraternities had a more religious and social focus. These brotherhoods feasted while they discussed elements of the faith. For example, most large cities across Europe were home to a confraternity of Corpus Christi, devoted to the doctrine of transubstantiation. They sometimes planned processions,engaged in civic activities, and provided various forms of charity. Other confraternities planned public events, such as the production of a cycle of plays depicting the life of Jesus during the week leading up to Easter. In all of the confraternities, laymen heard mass together, listened to sermons, and studied the complexities of the faith.

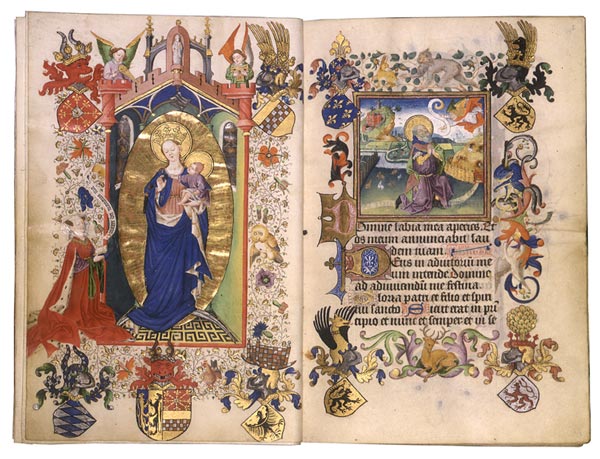

This deepening of the Christian education often started at a young age. In wealthier families, mothers taught children the prayers and stories of the Christian faith by reading them passages from the books of hours. Although the majority of these manuscripts were in Latin and therefore not immediately intelligible to children, they increasingly appeared in the vernacular during the 1300s and 1400s. They typically contained a calendar of Church feast days (of which there were dozens), passages from both the Old and New Testaments of the Vulgate Bible, a selection of psalms from the Old Testament, passages from the Gospels that often accompanied the lives of saints, and prayers, such as Ave Maria (“Hail Mary”) and Pater Noster (“Our Father”). Prior to the first use of the printing press in Europe (see below) in 1450, the ownership of a book of hours was a status symbol for medieval families. Aristocratic families commissioned ornate volumes with gold leaf and elaborate imagery, while less wealthy families were satisfied with fewer costly images. In general, these books contributed to an increase in literacy across much of Europe, especially among the more prosperous members of society.

The proliferation of mystical tracts during the 1300s and 1400 constituted another element of Christian piety that stimulated literacy. Mystics recounted their spiritual journeys in order to cultivate a direct, personal relationship with God. Numerous mystical tracts emerged as the declining prestige of the clergy encouraged Europeans to look after their own salvation rather than to rely on the corrupting influence of Church leaders. This trend accompanied the publication of works by Dante, Boccaccio, and Chaucer, all popular authors who wrote in the language of commoners and who ridiculed the leadership of the Church. Although one of the most popular mystical works of the early 1400s, the Imitation of Christ, initially appeared in Latin, translators soon rendered it into English, Dutch, French, and German. Because the subject matter of these works often bordered on heresy by minimizing the importance of sacraments, priests, and rituals for salvation, several of them, such as the Imitation of Christ and the Cloud of Unknowing were written anonymously, although later generations have been able to identify the authors with varying degrees of certainty.

One of the most fascinating mystics of the late 1300s and early 1400s was Julian of Norwich. After a near miss with death in the 1370s, Julian described her divine encounter in her Revelations of Divine Love, which depicted God as more feminine than masculine. The God that Julian had encountered possessed a motherly nature. Such ideas were contrary to the patriarchal vision of God that the Church authorities portrayed. Afraid to attach her name to her writings, she wrote them anonymously in her cell, a small room in a church in Norwich England. Later, local nuns collected and preserved her manuscripts. She became such a celebrity and revered religious figure that the Church leaders never interrogated her about her beliefs.

As the trends toward literacy, mysticism, and associations of pious lay people converged, the growing middle class of Europe formed movements that took advantage of the Church’s declining ability to control religious beliefs. During the 1320s, a movement known as the Brethren of the Free Spirit shocked Church authorities because of the diversity of their beliefs, which included autotheism, the merging of the soul of a person with the soul of God, and an erotic union of the individual with Christ. These ideas were fairly common in mystical tracts and in the beliefs of the beguines and their male counterparts, the Beghards. The movement spread widely from Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire to France, the Low Countries and the northern Italian peninsula. A decade later in Bavaria, Switzerland, and along the upper Rhine River, a group of mystics, who called themselves the Friends of God, included both lay people and clergy devoted to the reading and writing of mystical works. Perhaps the largest of these movements arose in the Low Countries on the Lower Rhine and then spread into the northern Empire. Known as the Devotio Moderna, this group initially consisted of lay people but soon became mostly members of the clergy. They called for Church reforms and for members of the clergy to return to monastic values of celibacy, hard work, and obedience. Led by a well-educated son of a civil servant from the Low Countries, Gerard Groote (1340-1384), they formed segregated but mutually supportive devotional communities of men and women, including many beguines. These communities read Christian texts and sometimes preached without permission from Church authorities in urban areas. They eventually influenced the likely author of the Imitation of Christ, Thomas à Kempis, who also refrained from attaching his name to a mystical tract. Although they faced some hostility from the Latin Church, their oppression was relatively mild compared to other groups, such as the Brethren of the Free Spirit earlier in the 1300s.

The vigor of Christian devotion during the Late Middle Ages was pronounced. Although some expressions of high medieval enthusiasm, such as cathedral building, processions, pilgrimages, pogroms, and the attachment to saints, not only persisted but also strengthened, other forms of religiosity, such as crusading, withered. Still practiced by a subset of nobles, by the 1300s crusading had little of the popular appeal that was evident during the First Crusade. Nevertheless, the expression of popular piety continued to evolve in civic rituals, loosely knit religious communities of beguines and beghards, formal institutions such as confraternities, and private gatherings. Mothers who could afford books of hours read stories of female and male saints to their children. Beguines and beghards read and interpreted the Bible, often in seclusion, lest their Bible reading provoke the authorities. While it might seem strange to imagine Bible reading as a subversive activity, the Church considered it as such when conducted by laypeople without supervision during the early 1400s. The breadth and depth of piety expanded, especially literate piety, oftentimes outside of the control of the Church authorities.

This combination of the decline of the prestige of religious authorities and of intense religious devotion provided the context for the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s. By then, popes such as Alexander IV, Julius II, and Leo X openly bribed their way into positions of leadership in order to advance their families’ dynastic ambitions. They lacked moral authority, and the papacy lost much of the prestige that it gained during the High Middle Ages. Meanwhile, pious believers chafed at the visible corruption associated with these dynastic wars, the sale of Church offices, and the sale of indulgences. As we will see below, the introduction of the printing press proved to be a catalyst for the revolutionary potential of these two trends: the declining prestige of the Church hierarchy and the intensifying religious devotion. In the meantime, let us turn to another catalyst for revolutionary change.

The Development of Gunpowder Technology

Beyond its chemical properties, gunpowder proved to be an explosive element of European social and political development as it became part of the transformation of warfare that had emerged during the early 1300s. Unlike the printing press, which was relatively simple, visible, and easy to comprehend as a form of technology, gunpowder involved a combination of invisible chemical processes and complex metallurgical skills that were not well understood during the Late Middle Ages. The ingredients of gunpowder were only part of the problem. The presence of saltpeter in a mixture of charcoal and sulfur attracted moisture, and the concoction was rendered unreliable when damp. In addition, the forging of accurate and reliable cannons was a tricky business. The length of the cannon and the size of the bore, where the cannonball exited, had a profound impact on the accuracy of the weapon. The casting of iron was difficult to perfect for cannon production, and wrought iron was inferior (too weak) for this purpose of containing an explosion. Alternatively, bronze was too expensive to mass produce. All of these factors hindered the development of gunpowder technology for several centuries.

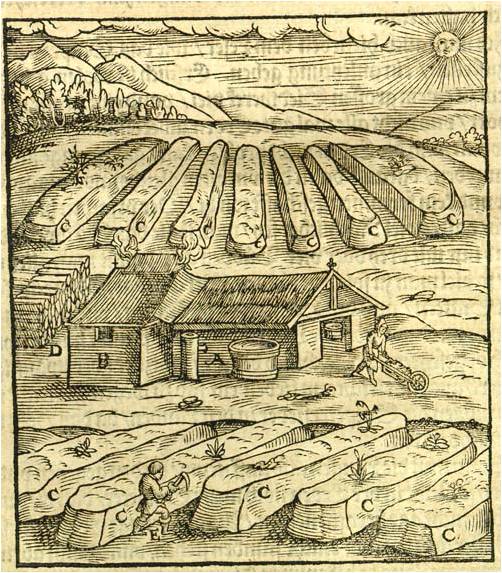

The first European to document the ingredients of gunpowder was a Franciscan friar, Roger Bacon (1220-1292), whose findings were buried in a voluminous work that he sent to Pope Clement VI in 1267 He described something akin to a firecracker and identified the ingredients of gunpowder as charcoal, sulfur and saltpeter. Although charcoal and sulfur were common enough in Europe, saltpeter had to come from India or China. The cost of saltpeter was also a significant obstacle to widespread experimentation, that is, until Europeans began manufacturing their own saltpeter from soil heavy in human and animal excrement in the late fourteenth century. Prior to that period, there were few documented instances of the use of gunpowder used in Europe. For example, Edward III may well have had a rudimentary cannon or two at the Battle of Crecy in 1346, and the Flemish likely used smaller, portable firearms called ribauldequins at the Battle of Beverhoutsveld in 1382. Neither of these episodes proved to be a turning point in the technology, partly because of the cost and partly because gunpowder in its simplest form, called serpentine powder, tended to absorb moisture, which caused its ignition to fail.

By the early 1400s the cost of gunpowder began to fall, but problems persisted with weapon design and construction. In 1415 the English employed very large cannons in the siege of Harfleur as they revived their efforts to conquer France. Equipped with approximately a dozen large cannons, bearing the names of “London,” “Messenger,” and “The King’s Daughter,” Henry V (r. 1413-1422), battered the walls of Harfleur, and despite excellent defensive measures, the city capitulated within five weeks. The bronze cannons were so heavy that Henry could not bring them with him on the rest of his overland campaign. Still, the cannons radically reduced the amount of time needed to besiege a well-fortified port city.

During the following decade the Bohemian opponents of the papacy and of the Holy Roman Empire, called Hussites, after the martyred Jan Hus (described above), figured out a solution to this problem. Unlike Henry V, they were not so much interested in siege warfare as they were in field warfare. Led by the blind and brilliant military commander, Jan Žižka (1360-1424), the Hussites consisted of a collection of peasants and middle-class Czechs who sought more religious freedom. Žižka improvised a highly mobile and effective fighting formation by adapting wagons commonly possessed by peasants into

Wagenburge (wagon fortresses). Equipped with a combination of crossbows, hand cannons, medium caliber cannons, and a few large cannons, all of which they packed very closely together in a powerful formation, the Hussites won a series of victories against the imperial forces before the papacy relented and granted the more moderate faction of Hussites the right to consume the Eurcharist in both forms in 1434.

The Hussites’ success with small and medium caliber artillery, which had the advantages of mobility and accuracy, also proved effective in siege warfare. During the 1440s and early 1450s, the French crown developed the first siege trains. Consisting of approximately 30 smaller cannons, called culverines, which horses could easily maneuver into position, the French recaptured fortresses that the English had taken from them between 1415 and 1435. Well supplied and highly organized, the French forces found the culverines much more accurate than the large cannons of a generation earlier. With longer barrels and smaller bores, the culverines shot cannon balls instead of stones. Rather than relying on one large boulder hurtling somewhat haphazardly toward a target, the French situated their siege weapons where they would be most effective. Then, they battered a chosen target with more precise and repeated fire. The results were so effective that within a decade they recaptured virtually all of the conquered dominions of the French crown between 1445 and 1453.

By 1494 the French demonstrated their expertise with siege weapons. They marched and rode into the Italian peninsula with a siege train of some 50 cannons. No Italian city-state was prepared to repel such an invading force, and the French king, Charles VIII (r. 1484-1498), seemed to achieve what so many German emperors had not. His conquest of Naples in 1494 sent shock-waves across the Italian peninsula and much of Europe. For a time it seemed as if gunpowder had rendered castles and city walls obsolete. For centuries defensive positions and defensive tactics had been more reliably effective than offensive weapons. Gunpowder reversed that relationship increasingly during the 1400s and into the early 1500. By 1550, expensive fortification programs made many cities difficult to besiege and the advantages of defensive positions reemerged by the late 1500s.

Still, gunpowder certainly proved revolutionary in the sense that it ultimately rendered mounted shock combat virtually useless. The introduction of corned powder (so called because the size of the grain was similar to that of a kernel of corn) in the late 1400s and early 1500s improved the effectiveness of small arms, called arquebuses and muskets. By 1525 Spanish musketeers gunned down French cavalry charges with deadly accuracy. In addition, more reliable firing mechanisms appeared by the 1520s; the wheel-lock firing mechanism replaced the match lock ignition, and pistol manufacturers in the guilds took advantage of the innovation. These changes further strengthened the trend toward large armies, dominated by infantry formations that persisted into the modern period. Similar to the longbow and the pike, the musket further entrenched the growth of large armies, manned by non-elites. Although rulers continued to depict warfare as a noble and chivalrous affair, muskets, culverins, pistols, and cannons contributed to the increasingly bloody nature of conflicts in European warfare. And as Europeans gradually fought more wars overseas, the effectiveness of these weapons facilitated their domination and exploitation of foreign lands.

Humanism, the Italian Renaissance, and Innovation

The horrors of famine, war, and plague accompanied one of the most innovative periods in European history. Although some historians have viewed the Italian Renaissance as more of a modern than a medieval phenomenon, innovations in literature, sculpture, painting, architecture, and engineering, which we often associate with the Renaissance, were well underway by the time the Hussites fought under the twin banners of the goose and the chalice. Unlike earlier renaissances, such as the Northumbrian or Carolingian Renaissance of the 700s and 800s, the Italian Renaissance of the 1300s and 1400s occurred outside of the monasteries. Although members of the clergy participated, the influence of the merchant class in the period’s greatest achievements distinguished it from early periods of intellectual vigor. The prosperity that the Italian city-states had enjoyed since the time of the crusades increased the size of the middle class and provided the necessary capital and educational opportunities that enabled the renaissance of the 1300s and 1400s.

By the onset of the Black Death in the mid-1300s one of the principal intellectual trends behind the Italian Renaissance was well underway: humanism. Inspired by Dante’s encyclopedic understanding both of Greco-Roman and of Judaeo-Christian textual traditions in the Divine Comedy, scholars increasingly sought to uncover, portray, and understand the cultures of the ancients. In part, they were motivated by the belief that ancient writers had access to lost secrets and knowledge that had fallen out of circulation since the fall of Rome. They were also interested in developing a form of education that met the needs of the middle class. Lawyers, notaries, bankers, merchants, doctors, and bureaucrats found the scholastic methods that dominated the medieval universities poorly suited to their needs to write contracts, letters, and practical documents. They sought more advanced literacy to improve the precision and nuance in their communication. Since the early 1300s, Italian scholars had increasingly undertaken the time consuming processes of transcribing, translating, and interpreting Greek and especially Latin texts, not only to improve their understanding of the past, but also to enhance their skills in writing and public speaking.

The widespread mercantile and commercial interests of republics, such as Florence, Venice, Siena, Lucca, and Genoa, created a market for tutors who could teach these language skills. All of these republics had assemblies where public speaking was a valuable asset. Speaking to assemblies and senates, merchants sought to shape tax and trade policies; more privately, they needed to read and write effective contracts. Similar to the sophists in ancient Athens, humanist scholars were experts in language, and wealthy merchants hired them as administrators for their businesses and tutors for their children. They taught poetry, history, rhetoric, and grammar. Humanists also understood the intricacies of word choices, syntax, and punctuation, and some could examine an ancient text and determine with precision the century of its creation based on this knowledge. Others became obsessed with the ancient writings of Cicero, the ancient Roman statesman and advocate of cultivating knowledge in the humanities. Most of them developed a passion for understanding the language and culture of the Roman Empire.

Among the most accomplished and influential of the early Italian humanist scholars in the 1300s were Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) and Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). Sometimes referred to as the “father of humanism,” Petrarch was an accomplished poet who traveled around Europe collecting manuscripts in order to study the culture of the ancients. By the 1340s he had become an international celebrity who received recognition and honors from wealthy patrons. Convinced that Europe had undergone a dark age since the fall of Rome, he advocated for improvements in literacy and learning. By 1350 he had formed a close bond with Boccaccio, who was in the employ of the republic of Florence just as the city was recovering from the Black Death. The meeting occurred when Boccaccio was also just completing his influential collection of 100 short stories, The Decameron. Heavily influenced by Dante’s Divine Comedy, the Decameron was also one of the great works of fourteenth-century vernacular literature. Petrarch was partly responsible for encouraging Boccaccio to shift his emphasis to mastering ancient Greek and Latin. This encouragement eventually led Boccaccio to write Genealogia deorum gentilium (The Genealogy of the Pagan Gods), a work that inspired later efforts to explore the intricacies of Greco-Roman religions.

Boccaccio and Petrarch were literary humanists, meaning their primary interests were in language and literature. Like most humanists, they were involved in both the active and contemplative spheres of life. Similar to Chaucer a generation later, they both worked as diplomats. This interest in both intellectual and practical matters was characteristic of humanist endeavors, and it promoted the growth of humanist administrators both in public and private capacities. The papacy, the Kingdom of Naples, and the northern Italian city-states, especially Florence, sought humanist scholars to administer their governments. One such administrator was Poggio Bracciolini who spent the better part of five decades working for various popes. When he was not actively employed in Rome, he was following in the footsteps of Petrarch by searching monasteries for lost or forgotten manuscripts that documented the histories of the Greeks and Romans.

The humanists’ influence extended to non-literary spheres as well. By the late 1300s, the republic of Florence was becoming the epicenter of the humanist movement. Its city leaders sought to build a cathedral that reflected Italian and especially ancient Roman heritage. A Gothic cathedral, which reflected the culture of the Franks, was out of the question. The French, from such a perspective, were barbarians in comparison to their Roman cultural superiors. Florence’s cathedral was to be as ambitious and impressive as the pantheon in Rome and the domed basilica of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia. However, 100 years into the construction of the Florentine cathedral, which began in the late 1200s, it became clear that no one had experience with constructing such an edifice. So, in 1418 the city held a competition; architects and engineers alike submitted models. Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), the son of a goldsmith, had studied Roman architecture and the pantheon in particular for the better part of two decades. He won the competition and set about overseeing the construction of the largest domed cathedral in Christendom. The feat was all the more impressive because the workers did not rely on scaffolding to support the dome while it was under construction.

In addition to being an architect, Brunelleschi was an artist and engineer. His interest in architecture required that he study geometry, which helped him to arrive at a scientific approach to linear perspective, the portrayal of three dimensional scenes on a two dimensional surface, such as a canvas or a piece of wood. Although he was not a man of letters, he wrote his calculations and plans for the cathedral in code so that no one would steal his design, and he developed several inventions to facilitate the construction of the cathedral. One of his most successful contrivances was a very large hoist that lifted building materials to the construction workers who were hundreds of feet above, on top of the cathedral. One of his least successful inventions was a paddle-wheel boat that he designed to transport marble and other building supplies up the Arno River to Florence. After receiving one of the first patents in history for the boat’s design in 1421, Brunelleschi completed its construction in 1427. It sank with a valuable load of marble, bound for the cathedral, on its maiden voyage that year.

A significant influence on Brunelleschi’s ability to weather such challenges was his ability to attract wealthy patrons, in particular Cosimo de Medici (1389-1464). The Medici family had become wealthy during the late 1300s and early 1400s, when the Medici Bank was one of the principal sources of finance for the Roman papacy. Although Cosimo was very involved in the running of the operation, he also committed a large portion of his substantial wealth to patronizing painters, sculptors, architects, and humanist scholars. He went on several manuscript hunting expeditions and assembled the first public library in Florence. For centuries intellectuals and artists had been dependent on patronage to sustain their work, and the Medici family could boast some of the most prolific patrons in European history. They commissioned scores of churches and monasteries, not only in Florence, but also in cities across Europe. Cosimo’s grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492), was every bit his equal in this regard. He commissioned works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michaelangelo, Botticelli, and many others. Medici patronage, therefore, funded many of the great works of art and architecture that we associate with the Italian Renaissance.

Despite its benefits, patronage certainly had its drawbacks. Artists and intellectuals needed to avoid angering their patrons. Failure to do so could mean loss of funding or exclusion from the communities of artists and intellectuals. One humanist scholar, Lorenzo Valla (1407-1457), displayed such an uneven temperament and a propensity to argue that he spent most of life traveling between various universities and patrons, even though his father and many of his acquaintances worked in his native Rome for the papal curia. Around 1440 Valla wrote his most famous piece, De falso credita et ementita Constantini Donatione declamatio, which declared that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery. He penned this broadside against papal power while in the employ of Alfonso V of Aragon, who was in the midst of a territorial dispute with the pope. Valla employed his formidable skills as a master of Latin to demonstrate that the work could not possibly be what it claimed. For centuries, various popes had claimed that the document hailed from the fourth century when the Emperor Constantine left Rome and placed the western half of the Roman Empire in the hands of the bishop of Rome. Valla’s analysis refuted these assertions by pointing out the poor Latin grammar and the use of the term “satrap,” which was not in use in Latin in the 300s, when it was allegedly composed. The messy Latin made the donation look like a poor piece of writing rather than an official document. Other humanists agreed with Valla’s assessment. Within a decade of Valla’s argument, despite his difficult personality, he found employment in the papal curia under the papacy of Pope Nicholas V, an advocate of humanist endeavors.

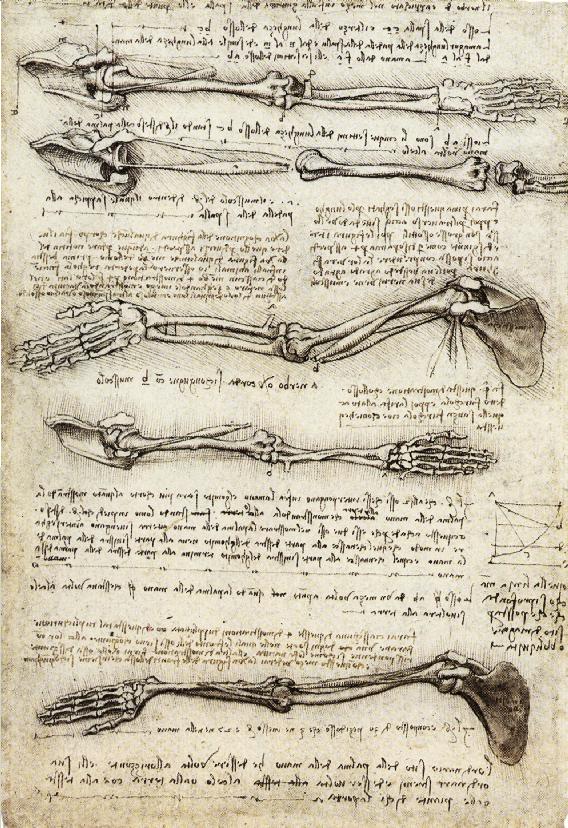

In the case of the Medici, their proclivities for humanist studies and the revival of elements of Greco-Roman architecture were well-known to the artists and intellectuals seeking patronage during the period. However, some artists were less enthusiastic about the humanist project of recovering lost ancient knowledge. One of these artists was Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). He certainly admired and studied the engineering drawings of Brunelleschi, who died six years before he was born; however, Leonardo’s interests were even more varied than Brunellischi’s. He pioneered the study of anatomy, when the Church forbade dissections of human cadavers. He engaged in the study of botany, engineering, and astronomy in addition to his well-known success in art. Although he completed some work in Florence, many of his most innovative accomplishments occurred under the patronage of the Duke of Milan and the King of France. His genius inspired his contemporaries, as well as future generations.

By 1494 the Medici position as the de facto power brokers and patrons of Florence became precarious as religious enthusiasts sought to cleanse the city of sinful influences, including depictions of pagan culture. On the day before Lent in 1497, the city authorities hosted a bonfire of vanities where authorities encouraged citizens to burn books, sculptures, paintings, clothing, mirrors, cosmetics, and anything else deemed sinful. The Medici had fled the city three years earlier as Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498) and a group of zealots enforced an austere set of mandates on the Florentines. Without the protection of a patron, artists such as Michaelangelo, who had grown up at the home of Lorenzo the Magnificent, left Florence for safer havens. Although many artists and the Medici themselves returned to Florence in the sixteenth century, Florence never regained its position as the epicenter of the Renaissance. Venice, Rome, Milan, and several other cities became new centers for intellectual and artistic achievement.

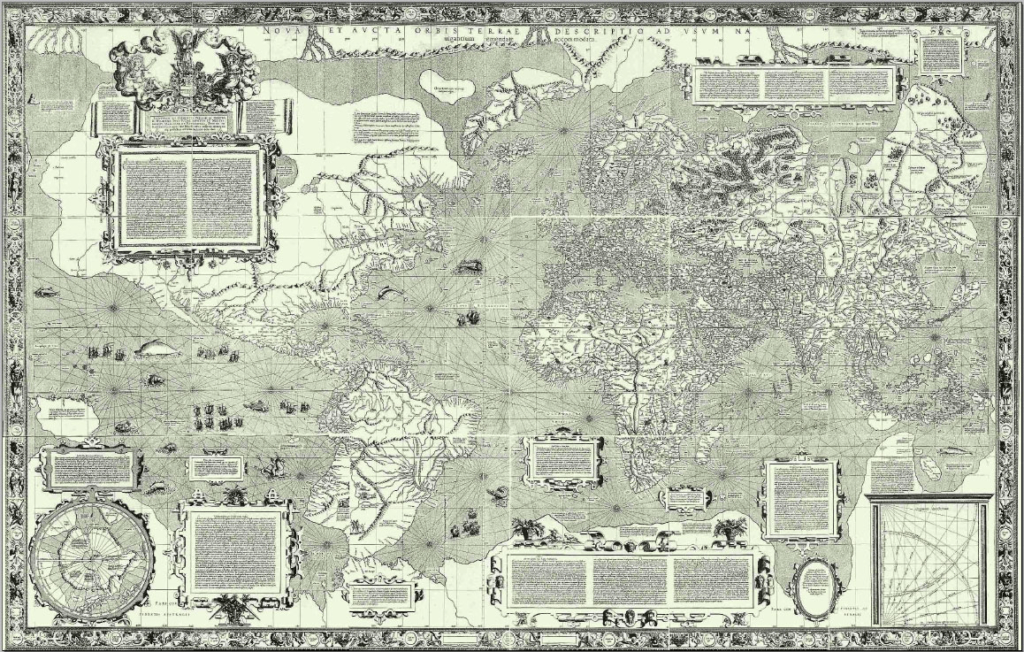

The innovative spirit that characterized the Italian Renaissance was not confined to the Italian Peninsula. By the early 1400s, Prince Henry (1394-1460) of Portugal, later known as Henry the Navigator, became the patron of an institute devoted to the improvement of navigation technology. He gathered the most accurate maps of the era, funded the design of ships that could sail into the wind, and sponsored voyages that charted the coast of Africa for the purpose of converting the native population to Latin Christianity. However, conversion for Henry and his disciples meant enslavement and the brutal treatment of dark-skinned people. The achievements of Henry the Navigator underscored the racism that found expression in European discourse during the Renaissance. The quest for domination of new lands unleashed an exploitative strain of European culture that was very much at odds with some of the high-minded ideals of the humanists to view humanity with reverence and respect.

The humanist movement continued well into the modern period and established the foundation for studies in the humanities. Generally, humanism functioned as an intellectual engine for the achievements of the Italian Renaissance. As its adherents traveled north of the Alps, where interest in ancient Rome had shallower historical roots, scholars applied what they termed “the new learning” to matters of religion. Armed with a mastery of Latin and eventually Greek, so-called Christian humanists encouraged Europeans to think of their religion in terms of its moral and ethical principles rather than a series of dogmatic doctrines, such as transubstantiation and the virgin birth of Jesus. It would be a mistake to conflate Christian humanism with Protestantism, because many Christian humanists remained faithful to the Church of Rome, while many of the founders of Protestantism were educated in traditional scholastic thinking. Nevertheless, the close textual analysis that was part of the humanist movement facilitated the turn toward more intensive Bible reading that characterized Protestantism in the 1500s.

Print and the Dawn of Modernity

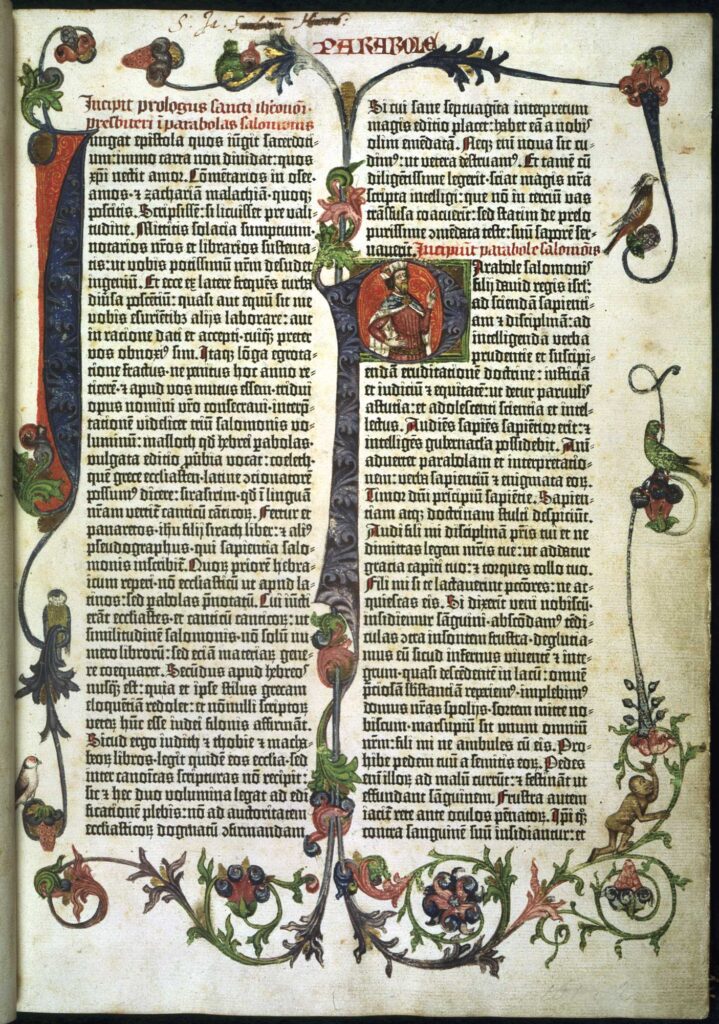

Although the Tang dynasty of the Chinese Empire had printed books by the ninth century CE, the impact of Gutenberg’s press in the mid-fifteenth century had a more profound impact in Europe partly because of a pent-up demand for books. During the Late Middle Ages demand for books increased significantly as more Europeans cultivated enhanced literacy. This skill enabled the reading and interpretation of lengthy and complex works, such as the Bible, saints’ lives, mystical literature, and the writings of Cicero and other ancient authors. The combination of the growth of pious reading and the rise of humanist studies induced the production of more books well before Johannes Gutenburg (1400-1468) began printing bibles around 1450.

Prior to the invention of Gutenberg’s press, the scriptoria located in monasteries and the lay copyists who worked in medieval guilds, such as the stationers guild, tried to meet demand by hiring more scribes. However, the time-consuming and error-prone process of copying books by hand resulted in the production of fewer books than the market demanded. In addition, the propensity of Europeans to eschew paper, which was inexpensive, in favor of animal skin (vellum), which was costly, hindered the use of woodcuts for block printing and increased the cost of book production. Patrons were partly responsible for this rising demand for books as they bestowed volumes to their clients as a sign of their magnificence. They commissioned multiple copies of ancient texts, sometimes recovered from humanist expeditions, while the demand for bibles continued to grow despite Church prohibitions against unsupervised lay Bible reading.